|

Edmonia Lewis, The Death of Cleopatra, carved 1876, marble, 63 x 31 1⁄4 x 46 in. (160.0 x 79.4 x 116.8 cm.), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Historical Society of Forest Park, Illinois, 1994.17.

Two

tons of marble restored, for viewing in the Smithsonian

Museum of American Art, Washington DC.

WASHINGTON POST 9 JUNE 1996 - AN AFTERLIFE FOR CLEOPATRA, CENTURY OLD SCULPTURE RESCUED FROM OBLIVION

It's been a long, harrowing journey. But after a century of neglect and abuse, the two-ton marble sculpture "The Death of

Cleopatra" -- a masterpiece by 19th-century artist Edmonia Lewis -- has found a home at the National Museum of American Art.

Modeled in Rome in 1875 by Lewis, an African American expatriate in her early thirties, this vastly ambitious depiction of Cleopatra just after her suicide, the deadly asp still in her hand, was created for the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. One history written shortly after the event called the work "the most remarkable piece of sculpture in the American section."

Yet two years later, after it was shown at the Chicago Interstate Industrial Exposition, the sculpture slipped into oblivion. A decade after that, so did the remarkable artist who had created it.

Thanks to recent scholarship, we now know that the owner of a racetrack in Forest Park, near Chicago, bought "The Death of Cleopatra" as a memorial for a favorite racehorse of the same name. It remained in place for nearly a hundred years as the racetrack became the site of a

golf course and later a

World War II munitions plant.

It wasn't until the mid-1980s, after Lewis's reputation had been resuscitated by a growing interest in African American art, that the work was rediscovered by a fire inspector in a salvage yard. It was badly damaged, defaced by weather, graffiti and several layers of paint. He enlisted his son's Boy Scout troop to clean and repaint it. All those layers, it appears, may have kept the elements from destroying the surface entirely.

By 1988, when the 5 1/2-foot-tall sculpture was given to the Historical Society of

Forest Park by the salvage yard, it was a virtual ruin, its hard, shiny white surface long since dissolved into a sugary texture. Details of hands,

jewelry, oak leaves and roses had worn away. The nose and chin, the asp and sandals, were broken off. Bad attempts at restoration had been made.

Only the coincidental discovery by NMAA sculpture curator George Gurney of a 19th-century photograph showing the work in its original state finally made an authentic restoration possible.

In 1994 the Historical Society of Forest Park gave the piece to the NMAA, which, in turn, undertook the $30,000 restoration. "Lost and Found: Edmonia Lewis's Cleopatra,' " now on view at the museum, celebrates that restoration and recovery. It also includes four of the eight other works by Lewis in the museum's collection.

Although the details of Lewis's life are murky, they appear to have been no less harrowing than those of her masterpiece. Born in 1843 or 1845, she was part Chippewa, part African American. Orphaned young, she attended Oberlin College in Ohio with the support of her brother, and excelled at drawing.

But even in this abolitionist outpost (the father of anti-slavery insurgent John Brown was among Oberlin's founders), she appears to have suffered unusual harassment. First, two girls tried to have her put on trial for attempting to poison them (the case was dismissed); later, someone accused her of stealing art supplies. No wrongdoing was ever proved, but Lewis was not allowed to graduate.

She moved to Boston where she studied with sculptor Edward A. Brackett, who taught her to model with clay. He also allowed her to produce medallions based on his portrait of Brown, made in jail just before Brown was hanged for his raid on Harpers Ferry. The sale of these medallions and portrait busts supported the young artist until she was able to move permanently to Rome, the sculptors' mecca.

Once there, she rented part of a studio that had belonged to the great neoclassical Italian sculptor Antonio Canova, whose work had inspired many American sculptors. She created figures such as the biblical Hagar (a slave who had a child by Abraham and was then cast into the wilderness) and neoclassical busts of poets like Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, whom she observed on the street in Rome. Commissions from American and English collectors included memorials such as the statue of Hygeia made for a female doctor buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery, outside Boston. Like flocks of other American sculptors in Rome at the time, Lewis also survived by selling marble cupids and copies of Old Masters, such as Michelangelo's "Moses." The Museum of American Art owns a "Moses," which is in this show.

It was the custom, then as now, for sculptors to create a work in the form of a clay model, which would then be enlarged and cut by Italian craftsmen. But there is one early piece in this show, "Old Arrow Maker" (inspired by Longfellow's "The Song of Hiawatha") that Lewis may have carved herself. And perhaps because you want so much to make contact with the artist here -- to somehow sense her touch -- it is easy to see a special intensity in the knitted brows of this Native American and his daughter.

Even "The Death of Cleopatra," her largest, boldest work, reflects what a deeply empathic artist she was. Though dealing with a woman from the distant past, a queen in neoclassical guise, Lewis has sought out and amplified Cleopatra's humanity.

Little is known of Lewis's later years. Her last major commission appears to have been an "Adoration of the Magi" for an unnamed Baltimore church in 1883, present whereabouts unknown. And what a pity. Four years later, Frederick Douglass wrote in his diary of traveling to Naples with the artist. But after that, both she and her reputation seemed to fade. One small work of hers was exhibited in the Columbian World Exposition in Chicago in 1893, but as part of a display of African American women's handiwork in the Woman's Building, not as art. The last sighting of her was in 1911 in Rome, but it is not known when she died or where she is buried.

Curator Gurney is hoping that even this small exhibition -- possibly the first solo museum show ever devoted to Edmonia Lewis's art -- will bring new information to light. The show will continue through Sept. 22. CAPTION: Sculptor Edmonia Lewis, photographed circa 1870 by Henry Rocher. CAPTION: "The Death of Cleopatra": Layers of paint and graffiti may have helped preserve the work, which lay long neglected in a salvage yard. CAPTION: "Old Arrow Maker" (1872): An empathetic view of a Native American and his daughter from Edmonia Lewis, who was part Chippewa.

By Jo Ann Lewis

Zenday

and Gal

Gadot are in the running to make biopic films of Cleopatra. We

think both actresses are wonderfully talented and have been

brilliant in other productions. Anyone playing the part of the Queen

of the Nile, is going to come in for criticism, as

will any movie, when the critics get their hands on it.

Cleopatra (69 - 30 BCE), the legendary queen of Egypt from 51 to 30 BCE, is often best known for her dramatic

suicide, allegedly from the fatal bite of a venomous snake.

Here, Edmonia Lewis portrayed Cleopatra in the moment after her death, wearing her royal attire, in majestic repose on a throne. The identical sphinx heads flanking the throne represent the twins she bore with

Roman general

Marc Antony, while the hieroglyphics on the side have no meaning.

Lewis was working at a time when Neoclassicism was a popular artistic style that favored classical,

Biblical, or literary

themes - thus Cleopatra was a common subject. Unlike her contemporaries who often depicted an idealized Cleopatra merely contemplating suicide, Lewis showed the queen’s death more realistically, after the asp’s venom had taken

hold - an attribute viewed as “ghastly” and “absolutely repellant” in its day (William J. Clark, Great American Sculpture, 1878). Despite this, the piece was first exhibited to great acclaim at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876 and critics raved that it was the most impressive American sculpture in the show.

Not long after its debut, however, Death of Cleopatra was presumed lost for almost a

century - appearing at a Chicago saloon, marking a horse’s grave at a suburban racetrack, and eventually reappearing at a salvage yard in the 1980s. The Museum has an online exhibit that documents the statue’s storied history and conservation.

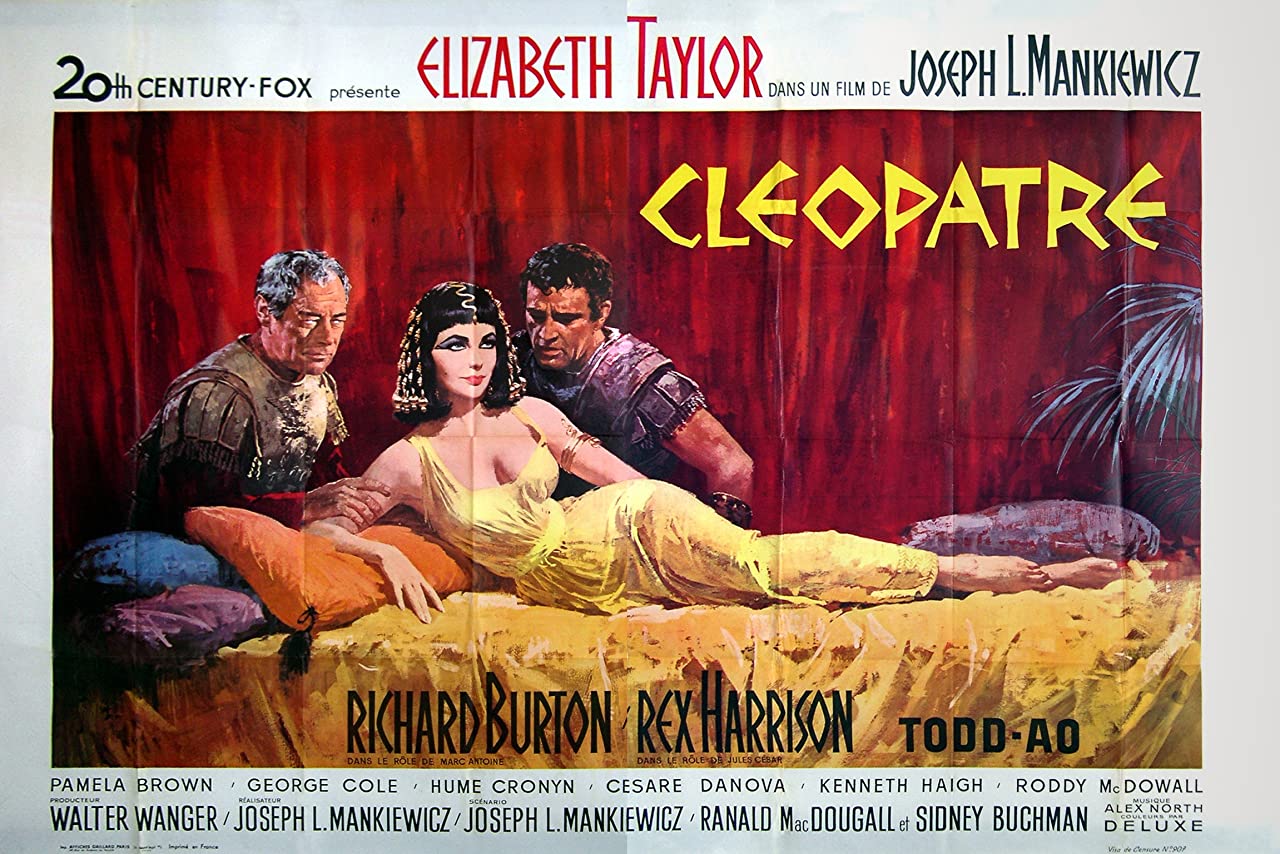

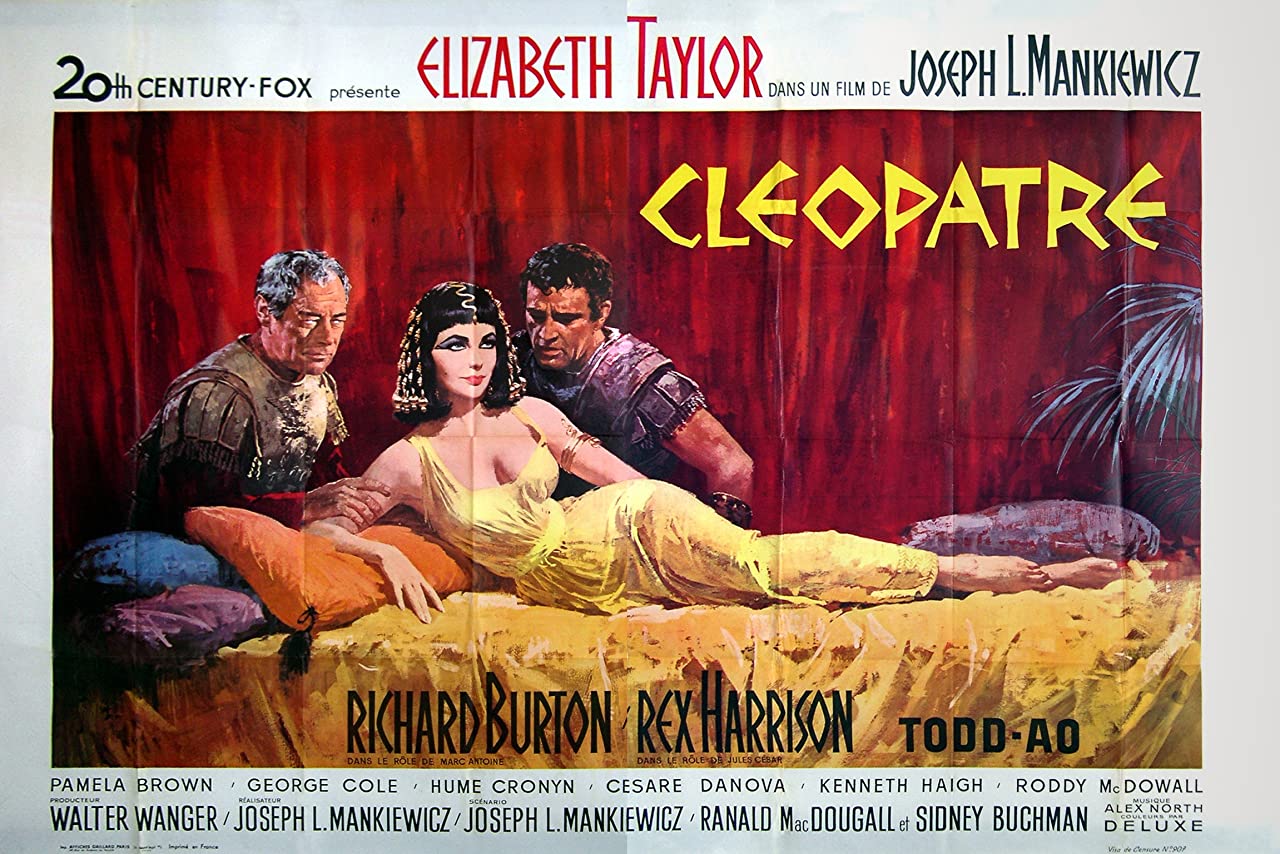

Sizzling:

Elizabeth Taylor, hit the mark, much as the real Cleopatra,

a real stunner.

When you visit the Smithsonian, you're entering the world's largest

museum complex, with approximately 157 million artifacts and specimens in its trust for the American people. Most of

their museums are located in the Washington,

D.C., area with two in New York City.

The Smithsonian museums are the most widely visible part of the United States' Smithsonian Institution and consist of 20 museums and galleries as well as the National Zoological Park. 17 of these collections are located in

Washington D.C., with 11 of those located on the National Mall. The remaining ones are in New York City and Chantilly, Virginia. The Arts and Industries Building is only open for special events.

The birth of the Smithsonian Institution can be traced to the acceptance of James Smithson's legacy, willed to the United States in 1826. Smithson died in 1829, and in 1836, President

Andrew Jackson informed Congress of the gift, which it accepted. In 1838, Smithson's legacy, which totaled more than $500,000, was delivered to the United States Mint and entered the Treasury. After eight years, in 1846, the Smithsonian Institution was established.

The Smithsonian Institution Building (also known as "The Castle") was completed in 1855 to house an art gallery, a library, a chemical laboratory, lecture halls, museum galleries, and offices. During this time the Smithsonian was a learning institution concerned mainly with enhancing science and less interested in being a museum. Under the second secretary, Spencer Fullerton Baird, the Smithsonian turned into a full-fledged museum, mostly through the acquisition of 60 boxcars worth of displays from the Centennial Exposition in

Philadelphia. The income from the exhibition of these artifacts allowed for the construction of the National Museum, which is now known as the Arts and Industries Building. This structure was opened in 1881 to provide the Smithsonian with its first proper facility for public display of the growing collections.

The Institution grew slowly until 1964 when Sidney Dillon Ripley became secretary. Ripley managed to expand the institution by eight museums and increased admission from 10.8 million to 30 million people a year. This period included the greatest and most rapid growth for the Smithsonian, and it continued until Ripley's resignation in 1984. Since the completion of the Arts and Industries Building, the Smithsonian has expanded to twenty separate museums with roughly 137 million objects in their collections, including works of art, natural specimens, and cultural artifacts. The Smithsonian museums are visited by over 25 million people every year.

MUSEUMS

11 of the 20 Smithsonian Institution museums and galleries are at the National Mall in Washington D.C., the open-area national park in Washington, D.C. running between the

Lincoln Memorial and the United States Capitol, with the Washington Monument providing a division slightly west of the center. Six other Smithsonian museums including the National Zoo are located elsewhere in Washington. Two more Smithsonian museums are located in New York City and one is located in Chantilly, Virginia.

The Smithsonian also holds close ties with over 200 museums in all 50 states, as well as Panama and

Puerto

Rico. These museums are known as Smithsonian Affiliates. Collections of artifacts are given to these museums in the form of long-term loans from the Smithsonian. These long-term loans are not the only Smithsonian exhibits outside the Smithsonian museums. The Smithsonian also has a large number of traveling exhibitions. Each year more than 50 exhibitions travel to hundreds of cities and towns all across the

United

States.

REFERENCE

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1996/06/10/an-afterlife-for-cleopatra/e3c246b5-c1b8-42c1-8705-22c2a0044ebe/

https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/death-cleopatra-33878

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1996/06/10/an-afterlife-for-cleopatra/e3c246b5-c1b8-42c1-8705-22c2a0044ebe/

https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/death-cleopatra-33878

|